Four months ago I wrote about this painting, a portrait of an Eighteenth Century farm labourer, which I bought at auction back in 2010. I had attributed it, on stylistic grounds, to ‘Mr Almond’, an itinerant painter known only from his portraits of the 3rd Duke of Dorset’s household in 1783. The portrait had a label on the back which read ‘Solomon Brigd(-) 1779.’

(c)JM

Since then, at the suggestion of Dr Matthew Craske who wrote about the Almond portraits for the National Portrait Gallery’s ‘Below Stairs’ exhibition in 2003, I have been in touch with Emma Slocombe, National Trust curator in the South East, who told me that the surviving portraits from the set all had similar labels on them to my painting. This was a result beyond my wildest expectations. But there was more. A Solomon Brigden, Carter, had been among the original sitters. Emma then put me in touch with Dominique El-Shirbini. Dominique has written a dissertation on the Almond set, and very kindly shared her research with me.

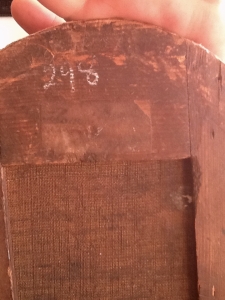

Mrs Sackville West very kindly allowed me to view the Almond set at Knole. There I met Emma and Dominique, who showed me a copy of an amazing document, a list written by John Bridgman, Steward at Knole in the years immediately after the Almond commission. Bridgman had recorded the names of each sitter from the set, including their occupation, and the year they entered the Duke’s service. Solomon Brigden, Carter, is no.32 in the list. The list also cleared up the question of the date on the back of the painting. I had assumed that 1779 was when the portrait was painted. Bridgman’s list shows that it was the date Solomon Brigden joined the household. Bridgman lists 48 portraits; 21 are still known; Solomon Brigden was one of the missing 27. John Bridgman also put a label on the back of each painting, which I was just able to read on Solomon’s, though the part where it would have said ‘Carter’ has become too rubbed to read.

(c)JM

Only four days before my visit, Mrs Sackville West and Emma had made an exciting discovery – the original receipt for the commission, which contained three new facts. Dominique noticed that it referred to 49 portraits, one more than Bridgman’s list. The artist had been paid £17 4s for the whole commission, 7 shillings or a third of a guinea each. By comparison, at the same date Sir Thomas Lawrence, then a 13 year old prodigy, was charging three guineas for a portrait the same size in pastel, and Francis Cotes was charging 20 guineas for a head. For such a beautiful and unique commission this was quite a bargain.

Furthermore, the receipt showed that the painter’s real name – given as Almond by John Bridgman – was Charles Almand. Was he originally French? Might he be the same as the Charles Almand who exhibited A View of the Island of St Helena in the East Indies at the Society of Artists in 1777? The only other painting attributed to this seafaring Almand is Breeze: View of Sailing Ships in a Channel sold at Skinner’s of Boston in 1995. I have asked them if an image survives. John Bridgman describes the painter as ‘itinerant’; perhaps he was very well-travelled indeed. Further attributions might build a biography for him.

Thanks to the information that Emma and Dominique shared, we can establish a tentative biography for Solomon Brigden. He seems to be the Solomon, son of Solomon, born in 1760. His father died in 1776, three years before our sitter entered the Duke’s service. During the Napoleonic invasion threat of 1803, a Solomon Brigden, described as a gardener, is listed as ‘willing to serve’ in the Withyham Militia. This may not be our sitter – Solomon was a family name and the Brigdens were a large family around Sevenoaks – but the Solomon Brigden who died in 1825 is almost certainly our man. His will, in which he is described as ‘Yeoman’, leaves a good estate to his ‘dear wife Elizabeth’ for life, then to be divided between his four sons and three daughters.

It was an incredibly successful piece of research, which left me rather awestruck. In a case like this you feel that the picture itself wants to be rediscovered. So all thanks are due to Solomon Brigden himself – who is now reunited with his old colleagues – to Dr Craske for his encouragement, and for all their very generous help to Emma, and Dominique, and, of course, to the Sackville-West family, then and now. The 3rd Duke of Dorset, the man who tried to introduce cricket to France when he was ambassador – and might have succeeded if it hadn’t been for the Revolution – was a remarkable patron. And the household he kept at Knole with his mistress the dancer Giovanna Baccelli was a remarkable household. The portraits he commissioned reveal the deep bond of affection that binds a great estate family together, and hint at the uniqueness of a man who employed some of his staff chiefly for their bowling ability.

Lastly, you have to thank John Bridgman, for making sure that every detail of the portraits and their sitters was recorded. This is incredibly rare. He too is a remarkable man. Bridgman’s Historical and Topographical Sketch of Knole in Kent; with a brief genealogy of the Sackville family (1827), with engravings after his own drawings, is a beautiful book. It’s a superb read, pithy and modern in its historical judgments and full of antiquarian zeal. The same spirit that listed the Duke’s staff in 1783 records the Earl of Dorset’s household, table by table as they sat at dinner in the 1620s. And it’s perfectly probable – as my Father first suggested – that ‘Solomon the Bird-catcher’ who ate at the Long Table in the Hall was an ancestor of the Duke’s carter a century and a half later.

Wonderful conclusion to your research James. Congratulations.

Solomon Brigden of Sevenoaks, Kent, who died in 1825 was my ancestor, the family originated from Hadlow, Kent.

Solomon’s wife was Elizabeth, nee Welch.

Fascinating to have found a portrait of him.

Margaret

Well done Margaret/James

Absolutely fascinating. John Bridgman was my great, great, great grandfather. He was with the Duke of Dorset from 1790 until he died, and was probably brought in to watch and manage the Duke’s spending. He married while he was there an Elizabeth Steer. After leaving Knole he set up a confectionary business in Vere Street off Oxford Street and became by Royal Appointment Confectioner to The Princess of Gloucester. He also collected paintings as one of his in in the museum at Norwich. He died in Wigmore Street in 1830. I am descended from his son Rev Arthur A bridgman then through his son Herbert A Bridgman who married the great granddaughter of Paul Colnaghi the art dealer. Herbert son Ronald A O Bridgman was my mother’s father. Do you know any more about John Bridgman?

Yours

Timothy Morgan-Owen

What a remarkable life, thank you very much for this – he was obviously a talented and very dedicated man. His labelling and cataloguing of the servant portraits is a godsend and so rare. You know more about him than I do, so there’s nothing I can add, sadly. But I will pass your information on to Knole. I’m sure they’d be very interested. My email is jramulraine@yahoo.co.uk. If you send me yours I can pass it on to them in case there is anything they can add. Very best wishes,

James